The Four People in the Casino: A Mental Model for Public Markets

Every investor has a favorite metaphor for the stock market. My personal favorite is the casino, not because markets are random or because “you can’t beat the house,” but because casinos have a beautifully simple ecosystem. Four distinct roles, each doing something different, each necessary for the system to function.

Once you see public markets through that lens, a lot of behavior that seems confusing becomes almost embarrassingly obvious.

The four roles are:

The Casino Owner: the long-term, qualitative investor

The Pit Boss: liquidity providers and market makers

The Card Counter: quantitative arbitrageurs

The General Customer: unsophisticated or flow-driven participants

Let’s walk through how each one operates and how this maps almost perfectly onto public markets.

1. The Casino Owner: The Long-Term Qualitative Investor

The owner of a casino doesn’t obsess over what happens on a Tuesday. They’re not sweating individual hands of blackjack. Their job is to build and operate a business that will survive competitive pressure, regulatory changes, and recessions. They need capital allocation skill, political influence, discipline, and patience.

That’s exactly what great qualitative investors do. They purchase long-duration assets, manage risk across time, and allocate capital the same way an owner would. They think in terms of:

business model durability

reinvestment runway

management quality

competitive moats

multi-year variance

Their Sharpe ratio is lower because they absorb real economic risk. But their capacity is enormous. A casino can deploy billions into square footage, tables, and customer experience. A great long-term investor can deploy enormous capital into the productive capacity of the real economy.

Crucially, qualitative investors make money from economic value creation, not from other investors losing. They’re participating in the positive-sum growth of businesses. Their edge is endurance and judgment.

2. The Pit Boss: Liquidity Providers and Market Makers

The pit boss doesn’t gamble. He’s not there to win or lose. His job is to make sure the game runs smoothly: no cheating, no stalling, no broken mechanics. He enforces structure and keeps the whole system functioning.

The equivalent in markets is the liquidity-providing complex:

high-frequency market makers

wholesalers

ETF authorized participants

internalization desks

These firms don’t care whether Pfizer or Nvidia goes up or down. They flatten out risk constantly, focus on spreads, and optimize execution quality. Their job is to keep the market operational.

In the casino analogy, the pit boss is employed by the house. In markets, this role is outsourced to independent firms. The economic role is the same. They are the infrastructure. They make the game possible.

Replace Citadel Securities with Jane Street and the market still works. Replace Buffett at Berkshire, and the entire organism changes. That distinction tells you everything.

3. The Card Counter: The Quantitative Arbitrageur

Card counters don’t want to run the casino. They want to extract small statistical edges before the casino notices. They have a high Sharpe ratio but tiny capacity. If they try to scale their strategy massively, the edge disappears.

This describes quantitative arbitrage perfectly. These firms run:

statistical arbitrage

market-neutral factor timing

short-horizon mean reversion

microstructure plays

cross-asset lead-lag strategies

They trade fast, hedge constantly, and treat risk like radioactive material. Their edges resemble card-counting edges: small, perishable, and dependent on discipline.

It’s no accident that many of the early quants literally came from poker and blackjack communities. They brought with them:

expected-value thinking

loss-control discipline

unemotional decisionmaking

Card counters don’t depend on economic growth. They depend on patterns and inefficiencies. They’re not building anything. They’re harvesting.

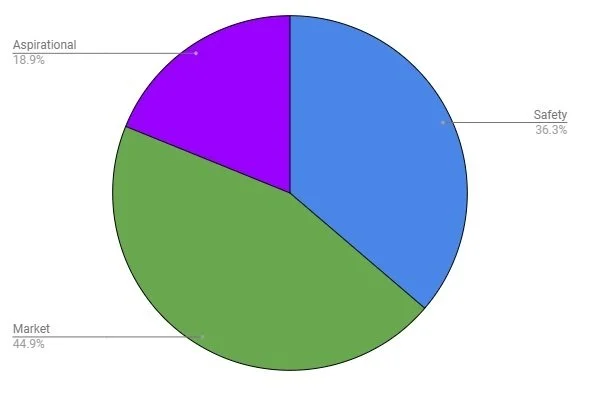

4. The General Customer: The Liquidity-Supplying Loser

Casinos need customers. They need the bulk of people who play the games, enjoy the atmosphere, and slowly lose money because the odds are against them.

Markets need this too.

This group includes:

retail traders following social media

index funds forced to rebalance

pensions with rigid mandates

leveraged players who get liquidated

corporate hedgers with non-economic objectives

portfolio managers facing quarterly career risk

They’re not stupid. They just have constraints. They’re playing a different game: liquidity, time, excitement, convenience, mandates. But they’re the reason edges exist. Their predictable flows create dislocations that both qualitative investors and quants feed on.

Without the general customer, there is no card counter edge and fewer opportunities for long-term buyers. They are the raw material of the market ecosystem.

Where Most Investors Go Wrong

Most people don’t know which role they’re playing. They think they’re the casino owner while behaving like a general customer. Or they think they’re a card counter when they’re actually just gambling. Or they think the pit boss is a genius money manager rather than a flow-driven infrastructure operator.

Once you identify your role, everything becomes clearer:

your capacity

your edge

your risk

your time horizon

your competition

your expected variance

A casino owner doesn’t try to play like a card counter.

A pit boss doesn’t try to steal the house edge.

A card counter doesn’t try to deploy ten billion dollars.

A general customer shouldn’t pretend they’re running a business.

Markets punish identity confusion.

Why This Framework Matters

This four-role setup actually explains almost every important dimension of investment strategy:

Sharpe vs capacity

Time horizon

Risk absorption vs risk neutralization

Flow-driven opportunities

Who benefits from volatility and who suffers

Each group fills a niche:

Casino owners absorb long-term risk and get paid in compounding.

Card counters extract micro-edges but can’t scale.

Pit bosses keep the system functioning.

General customers supply the liquidity and noise that make edges possible.

When you misidentify which role you’re playing, you get hurt.

When you understand your role, you can optimize for it.

The Punchline

Markets aren’t a casino because they’re rigged. They’re a casino because the ecosystem naturally separates into these four functional roles. Real investment insight starts with understanding where you fit into the ecosystem.