Real estate: to own, or not to own

I was first exposed to the real estate business through my grandpa and grandma. While I was in my early teens, my grandparents both worked as real estate agents in Long Island, New York. They were locally known as “The Dream Team.” One day after school, my grandpa took me out for a slice of pizza and I asked him to explain his work as a real estate agent.

Grandpa Jerry explained, “A real estate agent helps people buy and sell homes. In exchange for their help, the real estate agent keeps a small percent of the transaction price when a home is bought or sold. To put this “small percentage” in perspective, imagine you receive a small slice of a normal sized pizza, you can eat for a day. But if you receive a slice of pizza the size of a house, you can eat for a year.” My grandpa and I both love to eat pizza, and his explanation stuck with me.

For the last eight years, I’ve participated in the residential real estate market as a renter in Shenzhen, New York, and Cambridge. When you agree to be a renter, you agree to pay a fixed amount of money each month to live on your landlord's property. In exchange, the landlord needs to provide the renter with selected amenities and agrees to cover any capital expenditures required to mitigate wear and tear.

From a theoretical perspective, paying rent is very similar to entering into an interest rate swap contract. In this contract, as the renter, I agree to pay fixed, and my landlord receives floating. The landlord collects a fixed rent, pays variable expenses, and most importantly receives a floating rate of return equal to the capital gains or losses that come from changes in the property's market value. More recently, I've been re-thinking my decision to pay fixed and have started to think about taking the other side of the swap.

Of course, there is an academic answer to the rent/buy decision. The challenge is that the answer entirely depends on your assumptions. While these assumptions are uncertain, they can be estimated with varying degrees of precision. My friend Ben Willinksy recently passed me a model that the NYT created that helps you easily evaluate the theoretical approach to the rent/buy decision. The drawback to this tool is that it has 20 input assumptions. Like all assumption driven valuation models, slight changes to some of these assumptions can lead to a wide dispersion of outcomes.

I’ve always felt this theoretical approach to answering the rent/buy decision to be unsatisfying. A more satisfying approach would help me answer questions like:

- How good of an investment has buying a home been historically?

- What is the relationship of housing investment returns to other asset returns (stocks, bonds, cash, etc.)?

- What is the relationship between housing and inflation?

I wanted to approach the rent/buy decision empirically rather than theoretically. Remarkably, there was little long term research on housing returns until quite recently. In November of 2017, a team of five economists working in Europe and the US published a paper that comes a long way to bringing an empirical perspective to the rent/buy decision. The paper wonderfully titled, “The Rate of Return on Everything: 1870-2015” asks the question, what is the rate of return on the four core investible assets in the economy?* The researchers analyzed the real and nominal rates of return for Treasury Bills, Treasury Bonds, Public Equities, and for the first time, residential real estate for 16 countries from 1870 to 2015. Collecting and cleaning this data alone was a huge achievement.

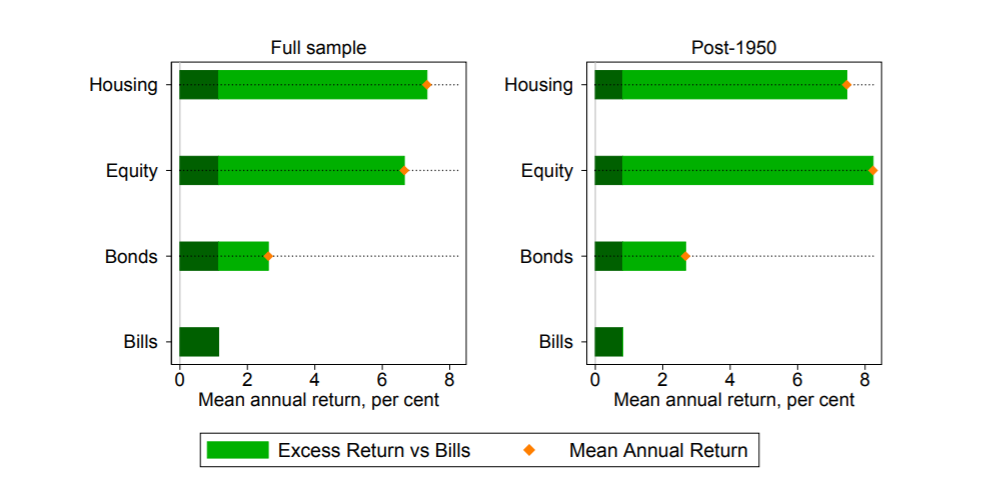

From this data, we can look at the historical returns, volatility, and correlations for each of the four core asset classes. I extracted the charts below from the paper and they help to provide a sense of the shape of the return distribution for each of the four asset classes. I pay special attention to housing below.

As is clear from the charts above, the average public equity market total return for this period was about 7% real and the average housing return was also about 7% real.** Even more intriguingly, housing returns appear to be lowly correlated with public equity markets and considerably less volatile. Housing also appears lowly correlated with inflation while equities are negatively correlated with inflation. Modern portfolio theory suggests if there are two assets with similar returns but low correlation with one another, then it is a strong argument for owning both assets.

The critical risks which could cause total capital loss to a housing investment are tail events including political risks, local economic decline, natural disasters and a sudden need for liquidity at a time when there are few interested buyers. Assuming these risks do not materialize, my instinct is that over long periods of time you are likely to receive a real return comparable to the returns described above.

The real housing returns described above include both rental income and capital gains. However, a landlord receives rental income only if they have a renter living on the property. If a home is owner occupied, then the owner only receives the capital gain return and the rental income is instead enjoyed as the benefit of living in the home. The chart below details the nominal returns for housing, decomposing it into capital gain and rental income. Looking only at the capital gain return gives us a good sense of what outcome we can expect should we become a landlord and live on our property.

So what should you expect as a homeowner? Nominal returns of 3.5% to 8.5% with an average of 5.7% over the sample period with half the volatility of equities. If the rest of your portfolio is composed of bills, bonds, or equities, these characteristics are even more intriguing. If you have the desire to become a landlord and manage renters, your returns can be considerably higher and the rental income comes with a volatility profile considerably lower than treasury bills which are often described as a risk-free asset.

After reading this paper, I am reasonably confident that taking the floating side of the swap is the optimal long-term decision.

End Notes:

*The paper was written by Oscar Jorda (Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco and the University of California Davis), Katharina Knoll (Deutsche Bundesbank), Dmitry Kuvshinov (University of Bonn), Moritz Schularick (University of Bonn), Alan Taylor (University of California Davis): Link to the paper is here.

**For reference, real returns are defined as nominal returns minus inflation.